Most folks reading our blog know the long disturbing history of how we have gotten to such a sad place in the US in our treatment of people with serious mental illnesses. You may find it interesting, as I did, to learn that President Reagan made a major change (see below), which resulted in diminished community resources.

“That began to change shortly after Ronald Regan was elected president in 1980. He ended earmarking of federal funds for this system of community mental health centers and instead substituted block grants to the states that they could use at their discretion. Almost all the states acted badly, cutting taxes rather than using the federal funding as before for community mental health.”

We need a federal plan that also involves the removal of the IMD exclusion. This mental health treatment exclusion is a parity violation. There is no such restriction on the length of stay or the number of medical beds in hospitals for medical conditions. Learn more about parity laws.

We need to focus on the people with SMI and not just general mental health!!

ACMI Board

Original article published by StatNews on July 9th by Allen Frances

President Biden’s ambitious infrastructure plan has a glaring omission: It makes no effort to redress the awful reality that the United States has the worst mental health infrastructure of any country in the developed world.

People with mental illness, their families, and society at large are suffering the tragic consequences of four decades of mental health defunding and privatization: 90% of psychiatric beds have been closed; the once-wonderful system of publicly funded community mental health centers has been gutted; crisis response teams are almost nonexistent; and the available pool of affordable housing meets only a fraction of what’s needed.

In the Middle Ages, people with severe mental illness were often chained in prisons, begged on the street, or languished in poor houses. In modern America, 350,000 people with mental illness are in jails or prisons (often for nuisance crimes that could easily have been avoided had treatment been available); 250,000 of them are homeless; and the average life span of those with severe mental illness is 20 years less than that of the general population. The rate of dying from Covid-19 was three time higher among people with schizophrenia than in the general community — the second biggest risk factor after age.

Law enforcement officers, sheriffs, and judges have become the most vocal critics of the brutal criminalization of mental illness and are now among the strongest advocates for improved community treatment and housing. Forcing scared and untrained police officers to be first responders for people with untreated mental illness puts them in untenable positions and is partly responsible for police brutality and shootings. People with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to die during a police encounter than other civilians.

And once in jail, people with mental health issues are difficult to manage, deteriorate further, spend disproportionate time in solitary confinement, and have prolonged stays (especially since they have no place to go and no treatment if released).

How did the U.S. get into this mess? Massive and rapid deinstitutionalization of people with mental health issues began in the late 1950s for several reasons: partly because effective antipsychotics had been discovered; partly as a humanitarian response to the horrors of the overcrowded “snake pit” state psychiatric hospitals; partly as a cost-cutting method (since mental health was often the biggest and most tempting item in state budgets).

The “new approach to mental illness” that President John F. Kennedy called for in a 1963 speech, which resulted in his signing into law the Community Mental Health Centers Act later that year, was a response to the great disruption caused by the rapid closure of the huge state hospitals. Community services were meant to provide a better life for people with mental illness at less cost to the states.

My first job working in a community mental health center in 1973 in New York City was thrilling. Patients who had languished for decades in state hospitals were able to enjoy much more normal lives with the benefits of medication and inclusion in the community. The U.S. became the world leader in community psychiatry and I was proud to be a psychiatrist.

That began to change shortly after Ronald Regan was elected president in 1980. He ended earmarking of federal funds for this system of community mental health centers and instead substituted block grants to the states that they could use at their discretion. Almost all the states acted badly, cutting taxes rather than using the federal funding as before for community mental health.

And the money saved by closing the expensive state psychiatric hospitals rarely followed patients into their communities to provide badly needed treatment and housing. Community mental services either closed or were privatized, and the newly private services routinely refused care to people with severe mental illness because they were usually uninsured and always very expensive to treat.

Eventually, deinstitutionalization turned into reinstitutionalization as prisons replaced hospitals as the biggest line item in state budgets. Under Reagan, the U.S. quickly went from having the best system of community psychiatric care in the world to the worst, and things have further deteriorated ever since.

It is not clear how much of Biden’s extensive physical and human infrastructure rebuilding plan will eventually be enacted into law. But it is crystal clear that rebuilding our country’s shamefully lacking mental health system is not part of the plan.

It is also clear why. Powerful lobbying forces in Washington are fiercely jostling to capture the money allocated to the infrastructure program. Whatever emerges will reflect how much political and economic muscle each industry can exert on the politicians doing the horse trading. In this battle of the titans, people with mental illness are voiceless and their advocacy groups lack political and economic muscle.

The care of people with severe mental illness is necessarily a public responsibility that has been neglected in our primarily for-profit private health care system. The United States has shirked this public responsibility more than any other developed nation on earth. The Biden plan is a sad lost opportunity to play catch-up on desperately needed mental health services and its exclusion of mental health means there is no hope in sight.

Mahatma Gandhi once said that a nation’s greatness is judged by how it treats its weakest members. By this standard, the United States is morally bankrupt and the very opposite of great.

Allen Frances is a psychiatrist, professor and chair emeritus of the Duke University Department of Psychiatry, and was chair of the DSM-IV Task Force from 1987 to 1994.

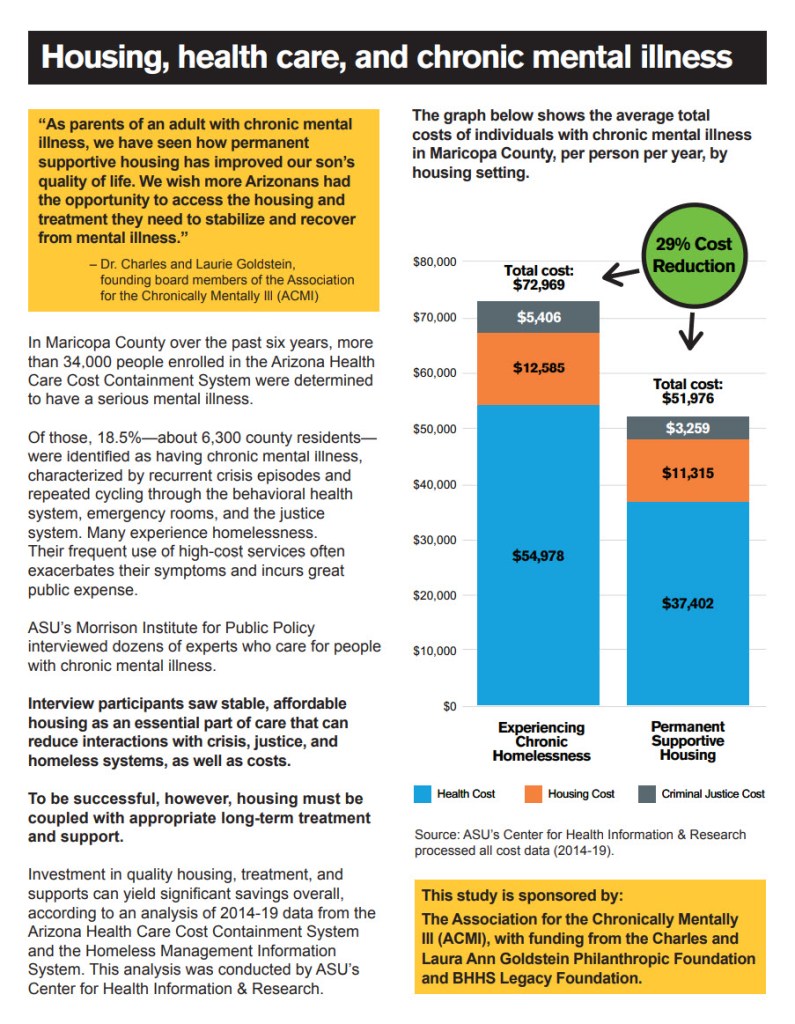

The results of the ASU research initiated by ACMI.

View the full report at:

https://morrisoninstitute.asu.edu/housing_is_health_care

This study examines how housing and in-home supports affect public spending on individuals with chronic mental illness in Maricopa County, Arizona.

It does so through a comparative analysis of average costs per person per year across three housing settings: permanent supportive housing, housing with unknown in-home support, and chronic homelessness.

Specifically, it analyzes costs for housing, health care, and criminal justice during the period of 2014-2019. It also features a small-sample (small-N) case study of a housing setting that provides individualized, 24/7 in-home support to individuals with chronic mental illness (CMI) who have high support needs, examining average costs per person before and after moving into that setting (2016-2019).

Finally, the study outlines recommendations from interviews with dozens of experts who work with and care for individuals with CMI in Maricopa County about reducing costs and improving care.

Read the complete report here.

Read a two-page handout based on the report here.

Watch the webinar describing the report’s highlights.

Read coverage of the report in The Arizona Republic.

Watch the “Housing is Health Care” Video Series, also available below.

We have an underclass in Arizona – our chronically mentally ill, most of whom suffer from schizophrenia. Society treats this sliver of people with serious mental illness just as cruelly and inhumanely as the lepers of antiquity or the untouchables of India. Many of these persons have no shelter, no bed, no toilet, no shower or bathtub, no running water, no electricity, and no reliable access to food, clean water, or medical care unless they are in jail.

Our public mental health care system is organized for and provides exemplary care for the 90% of Seriously Mentally Ill (“SMI”) persons who have insight into their illness and are mostly compliant with treatment. But, some SMI persons are chronic, i.e., they are so ill they believe the voices in their heads and their delusions are real, they suffer anosognosia (inability to recognize one’s clinically evident mental illness). They are mostly non-compliant with treatment. So, they recycle, repeatedly, through treatment programs, emergency rooms, hospitals, the streets, and jails in a hellish existence. Their physical and mental health deteriorates as their families abandon them or become exhausted, struggling to get care for them, and are blocked at every turn.

This underclass results from myths about mental illness, which permeate much of our public mental health care system and block chronically mentally persons from desperately needed care. As the father of a chronically mentally ill adult, I personally have been told each of the comments paraphrased in quotes below:

- Recovery myth: “All persons with SMI can recover and lead a normal life.” In reality, chronic mental illness is more like diabetes and can be managed but rarely, if ever, cured.

- Compliance myth: “All persons with SMI can ‘recover’ by complying with treatment in short-term residential programs, community living programs or independent living with ‘wrap-around’ services, combined, as needed, with assertive community treatment (‘ACT’) and occasional involuntary treatment (i.e., injections and short-term hospitalizations), regardless of the severity of their illness.” “He fails to recover because he chooses not to comply with our treatment protocols and rules, so he cannot continue in our treatment program.” The most severely ill are denied treatment because of the severity of their illness.

- Acuity myth: “SMI does not impair her ability to make good decisions and is no excuse for her inappropriate behavior.” In reality, schizophrenia is a physiological impairment of the brain which does affect judgment and behavior.

- Fairness myth: “All adults with SMI should be allowed to make their own medical decisions, to refuse treatment, to choose homelessness and never should be subjected to long-term involuntary care, regardless of the severity of their illness.” “Removing such liberty is unfair discrimination against the mentally ill.”

- Substance use myth: “It’s just illicit drugs.” ”We cannot treat his mental illness until he overcomes his substance use problem.” In reality, 75% of SMI persons who are chronically afflicted self-medicate with illicit substances for temporary relief from painful symptoms at some point in their life, which exacerbates their illness.

These myths coalesce into an unconscious, sometimes deliberate, and often-denied culture of blocking chronically-afflicted persons from care because “he won’t comply”; “he uses drugs”; or, “he’s an adult and makes his own choices.” In reality, she thinks the voices and delusions are real, and hence she cannot participate consistently in the treatment offered to the other 90% of SMI persons who have insight. She needs a caring system free of these myths, more flexible, more attuned to her individual needs, and more accountable to the public. And, she might even need long-term involuntary treatment, opponents of which sincerely believe and use these myths to block expansion of such treatment, unwittingly keeping this underclass in our streets and jails.

Dick Dunseath, father of a chronically mentally ill adult son / Carefree, Arizona

Founding member of ACMI board

Please join us to learn about the “Mapping the Costs of Serious Mental Illness” which was a two-year study commissioned by ACMI to determine various costs associated with serious mental illness. There will be a presentation followed by a Q & A session.

Register Now

Register in advance for this meeting: https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZYldOyrrjoqHdEvH6ccSIvuuvhqjVOG6_IJ

After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the meeting.

Weekend Legislative Roundup.

The following bills that seek to enhance the well-being of individuals and families with chronic mental illness in Arizona continue to move forward. Here’s where they stand and how you can help:

SB1059 – Clarifies current law requires that a person with mental illness and substance use diagnosis must be evaluated and not summarily dismissed due to the presence of drugs. The intention is to make treatment consistent.

Status: Passed in the Senate. Passed out of House Committees, currently waiting to go to House floor for a vote. Email all House members.

Action: Call and/or email your AZ Representatives. Email the Governor’s office and ask for his support.

SB1142 – A tax incentive bill for employers who hire people with serious mental illness. Sets the credit amount at $2 for each hour worked by an SMI employee during the calendar year, not to exceed $20,000, tax-paying business owner. Government agencies excluded.

Status: Passed in the Senate. To be heard in the House Appropriations Committee this Tuesday, 3/30, for a vote.

Action: Call and/or email the House Appropriations Committee members (emails below) and ask them to support. Call and/or email your AZ Representatives. Email the Governor’s office and ask for his support.

SB1716 – Currently, only 55 patients from Maricopa County can be at the Arizona State Hospital (ASH) — even when there are empty beds. ASH will no longer limit the number of patients who can be admitted based on the county where the patient lives. Admission should be based on clinical needs.

Reforms the existing ASH Governing Body (Governing Body) to operate without conflicts of interest: Most members will NO LONGER be employees of the Department of Health Services, which oversees ASH. Requires that the Chair of the Independent Oversight Committee (IOC) be invited to Board meetings and provided quarterly reports about human rights violations with patients. Improves transparency — requires Governing Body file annual reports with the Legislature that describe the treatment provides and what is working.

Patient safety improvement: ASH has an outmoded video surveillance system that puts patient safety at risk. We need a better surveillance system. The bill requires ASH to maintain a surveillance system with video and audio and appropriates $500,000 to do so. ASH administration has requested a new system last year and is currently in a Request for Proposal.

Status: Passed in the Senate. To be heard in the House Appropriations Committee this Tuesday, 3/30, for a vote.

Action: Call and/or email the House Appropriations Committee members (emails below) and ask them to support. Call and/or email your AZ Representatives. Email the Governor’s office and ask for his support.

SB1029 & SB1030 – Psychiatric security review board (PSRB) bill, SB1029, requires more information and reports for the Board to ensure that it treats patients fairly and protects the public. The Board now operates without enough information on patients when it makes decisions. The bill has a retired judge become the Chair, so the Board operates by fair rules.

Because the PSRB Board opposes any changes and claims that it operates perfectly, SB1030 ends the PSRB and sends the functions that the PSRB performs to the Superior Court in each county. This saves the state money and will ensure that patients get a fair hearing in front of a judge who follows the law.

Status: Passed in the Senate. Passed in the House Committees, waiting to go to the House floor for a vote.

Action: Call and/or email your AZ Representatives. Email the Governor’s office and ask for his support.

Here is a link to find AZ Representative’s email:

The Arizona Peoples Lobbyist – Your Voice – Your Choice (azpeopleslobbyist.com)

SB1786 – Prisoner Mental Health Transition Bill.

Status: Passed in the Senate. Passed in the House Committees, waiting to go to the House floor for a vote.

Action: Call and/or email your AZ Representatives. Email the Governor’s office and ask for his support.

SCR1018 – A Concurrent Resolution expresses support for community-based efforts to provide clinically appropriate care to individuals with chronic serious mental illness.

Status: Passed in the Senate. Passed in the House Committees, waiting to go to the House floor for a vote.

Action: Call and/or email your AZ Representatives. Email the Governor’s office and ask for his support.

Here is a link to find AZ Representative’s email:

The Arizona Peoples Lobbyist – Your Voice – Your Choice (azpeopleslobbyist.com)

ACMI would like to thank Senator Nancy Barto, the sponsor of these bills, for her tireless and heroic work on behalf of individuals and families living with chronic mental illness in Arizona! When you have an opportunity, please thank her as well.

We realize that everyone’s life is full; if you are unable to call or email but still want to help the chronically mentally ill, you can partner with us financially. ACMI is a group of dedicated volunteers; no one receives a salary. Your gift will go directly toward improving the well-being of people living with chronic mental illness.

Please contact your legislators by this Monday morning.

Here is a link to find their email:

The Arizona Peoples Lobbyist – Your Voice – Your Choice (azpeopleslobbyist.com)

Or call the Governor’s office at 1-602-542-4331 or email engage@az.gov

House Appropriations Committee members:

César Chávez cchavez@azleg.gov

Regina E. Cobb rcobb@azleg.gov

Charlene R. Fernandez cfernandez@azleg.gov

Randall Friese rfriese@azleg.gov

Jake Hoffman jhffman@azleg.gov

Steve Kaiser skaiser@azleg.gov

John Kavanagh jkavanagh@azleg.gov

Aaron Lieberman alieberman@azleg.gov

Quang H. Nguyen qnguyen@azleg.gov

Becky A. Nutt bnutt@azleg.gov

Joanne Osborne josborne@azleg.gov

Judy Schwiebert jschwiebert@azleg.gov

Michelle Udall mudall@azleg.gov

Your partnership in helping the chronically mentally ill and their families in our state is so appreciated, thank you!

Thank you,

ACMI Board

Courtesy of Unsplash photography

Courtesy of Unsplash photography

Every parent’s worst nightmare is the thought of possibly losing a child in an accident or to a serious illness. An even greater fear is the thought of losing a child to an abduction and never knowing where that child is or who the child is with. Moreover, no parent wants to see their child abused or to be an abuser.

I have lost a child……. to a serious mental illness and addictions.

I have lost a child to multiple “accidents” in the current mental health system in which I have tried to participate. I go to bed every night not knowing where my child is or who she is with. I face each new day with the fear that she did not survive the night. Every day I brainstorm and research what else I might do to find her and get her to a hospital where she can be helped. Occasionally, I get a call from a police officer who has had an encounter with her, usually for trespassing or loitering. The call is a result of recent missing persons’ report that I filed. I am told that she is “okay” by the officer, even if she is demonstrating psychotic behavior, dressed in appropriately for the weather, calling 911 because she believes that she has been run over by a truck, or staying in settings where assaults are frequent.

Because she has not been given proper care and limits are placed on those of us (family, primarily) who are trying to help her, the results are as follows: multiple arrests, jail time, cruel solitary confinement, car accidents, fines, court hearings, emergency calls to police and fire departments, hospitalizations for both physical and psychiatric treatment, rehabs, halfway houses, domestic violence calls, petitions, court ordered appointments at clinics, dental repairs from assaults, disease, property damage, job losses, and loss of all meaningful relationships of friends and family.

My “child” is an adult who is persistently and acutely disabled due to mental illness and addictions. I am told over and over by physicians, law enforcement officers, counselors and friends, “She is an adult. You can’t force her to get help.” “She has to hit bottom first.” “We can’t tell you if she has been admitted.” “She can be talking to a light pole, but unless she has threatened to harm herself or others, we cannot admit her.” “Since she is already under court ordered treatment, you cannot petition her for pick-up. She has been evaluated already. She just needs to show up for her meds at her assigned clinic.” These comments demonstrate the lack of understanding when it comes to mental health and addiction issues. People who are not thinking clearly cannot make decisions in their best interest. Their brain is lying to them and sending a false narrative. Hitting bottom often means death. What good is court ordered treatment, if once you get it you cannot be evaluated again should you have a setback in your mental stability! Most severely mentally ill people have a very difficult time managing their own medications and even getting to all of the appointments without assistance.

Based upon calls from the police, my daughter is most likely living in a box on the streets of Phoenix and has been there at least 10 months. Previous to her leaving my home, she had lived with me for a year. It was one of the nicest years we had spent with her. She had developed a few close friends, interacted with family again, paid off most of her fines, obtained a job, bought a car, traveled with us, and went to all of her appointments at the court appointed clinic.

There were two things that I think made the most difference in our daughter’s progress: parental involvement and a longer stay at the mental health hospital initially. Obtaining a lawyer and gaining temporary guardianship was the first step in being able to be more involved in her care. Additionally, the longer stay at the psychiatric hospital allowed her to be evaluated thoroughly, stabilized, and prescribed the correct medication. It was amazing to see the difference in how she interacted with us and life in general following her hospital stay. Previous stays in the hospital had been so short (3-7 days) resulting in her return to the streets.

What failed? Why are we back where we started over a year ago? I believe when a medication change took place through her clinic there was a set-back in her mental health at that time and her desire for meth increased. We (her legal guardians) once again admitted her to UPC due to psychotic behavior. She was then sent to a different hospital and there they changed her medication again rather than prescribe what she had previously taken successfully a year before. I believe if she had gone back to the same hospital and seen the same doctor, she would be in a different place now. Long term care offers a chance to stabilize and seeing the same doctor offers consistency in care. The out-patient clinics primarily serve as dispensaries of meds, not in-depth evaluation and continued care. When we sought to renew guardianship, this process was dead on arrival because our paperwork had to be completed by a psychiatrist. All of her appointments at her court ordered clinic had been with the equivalent of a PA.

We must increase the number of secure, mental health hospitals. Current numbers are grossly inadequate. The length of hospital stays must increase for the seriously mentally ill allowing time for proper evaluation, stabilization, medication, and a proper post hospital plan. We need supervised housing for the SMI once released from the hospital as a protection for the patient, family and the general public. Currently, many SMI patients find housing in drug rehab settings which are not set up for the SMI population. Others return to the street or with family who are not always equipped to provide adequate supervision and support.

For change to take place, we must not view mental illness/addictions any differently than we do someone with dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, autism, or delayed mental functions. We make sure that they are in a safe environment and decisions are made with their best interest at heart. The SMI are being neglected and not receiving the help they so desperately need. Just walk around downtown Phoenix to see how many of the SMI are living. We take care of stray dogs better than these precious human beings.

I hope our daughter can soon get the help she needs before it is too late. We have lived the nightmare and I have only shared a brief summary of this past year, not the previous twenty years.

Anonymous Parent (in order to protect my daughter’s privacy)

These are the families that ACMI advocate for. They are the most vulnerable.

Thank you for attending our online webinars; if you missed it, you could find the webinar and slides on our website. You will need to create a free account to view the webinars and downloads.

Who Are We Treating (And Not Treating) And Why?

By Dr. Michael Franczak of Copa Healthcare on Population Health trends in Maricopa County. He brings decades of experience into the conversation.

https://acmionline.com/downloads/

https://acmionline.com/webinars/

Signing up for a free account enrolls you into our newsletter; you may unsubscribe at any time.

Here are my thoughts about the IMS exclusion and appropriate treatment of people with serious mental illness. We need all the levels of care available in the continuum of care. Today in-patient care is significantly limited due to this archaic Medicaid rule.

In today’s blog from Pete Earley, he refers to a report by Steven Eida, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and editor of City Journal, and Carolyn Gorman, a policy analyst on issues related to serious mental illness who has served as a board member of Mental Illness Policy Org., a nonprofit founded by the late DJ Jaffe.

The Association for the Chronically Mentally Ill (ACMI) has championed the rights of the chronically mentally ill for more than three years. Our focus has been on creating appropriate housing for people with chronic mental illness, in other words, those people with serious mental illness who are not adherent to the current treatments and policies available to them under our Arizona behavioral health system. This year, we made efforts to reform our state psychiatric hospital, the Arizona State Hospital (ASH). This article is directly on point and aligns perfectly with our goals in trying to make people realize that this group of non-adherent SMI, who we choose to call the chronically mentally ill, are not well served by relegating them to the usual treatments available in the community, but, instead, frequently need longer-term treatment in level 1 psychiatric hospitals.

Also, after stability, when released to the community, they need more intensive supervision in order to treat their chronic psychiatric illness and have meaningful lives.

In addition, an upcoming study by the Morrison Institute, sponsored by ACMI, found that there were significant savings to the behavioral health system because of the decreased costs that resulted when this notch group of seriously mentally ill, the chronically mentally ill, are treated appropriately, safely, and humanely.

Charles Goldstein, MD

Pete Earley’s original article

Will Eliminating Old Rule Return “Snake pit” Hospitals Or Help Seriously Mentally Ill Americans Get Much Needed Long Term Care?

(2-26-21) A conservative think tank has joined a growing national chorus calling for an end of a federal rule that discourages states from building psychiatric hospitals and providing long-term, in-patient care for the seriously mentally ill.

The Manhattan Institute argues in a new report released this week that the Medicaid’s IMD Exclusion rule has outlived its usefulness and should be repealed.

President Trump’s President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice and the Interdepartmental Serious Mental Illness Coordinating Committee created by the Obama Administration also have called for dropping the rule.

What is the IMD Exclusion and why should you care?

It’s a rule that has been around since 1965 that discourages states from building and supporting large psychiatric hospitals and pushes them instead to provide community based treatment. The so-called “16 bed rule” accomplishes this by denying states Medicaid reimbursement for adults between the ages of 22-to-64 if they are treated in psychiatric hospitals and other facilities which have more than 16 beds. States must pay 100 percent of the cost of care for the seriously ill in most long-term psychiatric hospitals, compared to 50 percent for those treated in the community.

The new report’s authors, Stephen Eide and Carolyn D. Gorman, provide a thoughtful argument in favor of dumping the rule.

They document how difficult it is for parents and others to find hospital beds when someone is in the midst of a psychiatric crisis. It is not unusual for individuals to be turned away from emergency rooms or “boarded” in them for several days waiting for a hospital bed to become available. The lack of treatment beds also leads to individuals, who can’t get help, being arrested. The authors argue that Americans with serious mental illnesses simply can’t always get the long term help that they need in a community setting.

The 16 bed rule was enacted, in part, to put an end to warehousing patients in huge state hospitals, and those who support keeping it fear that state hospitals, once again, will become giant “snake pits” if the rule is repealed.

The authors of the Manhattan Institute report disagree.

They claim safeguards are in place now that weren’t years ago. Patients must be considered a danger to themselves or others before being held against their will in a state hospital. Many more treatment programs are available now than when state hospitals were the only choice. Federal laws, especially the Supreme Court’s Olmstead ruling, which requires individuals with mental illnesses be held in the least restrictive settings, will insure patients aren’t abused and forgotten in state hospitals. Plus, every state has a Protection and Advocacy Agency, specifically designed to investigate complaints about abuse in state hospitals and other long term facilities.

Modern psychiatric hospitals “are not designed as isolation wards” and “policies on seclusion and restraint are drastically changed” from the old days, the author’s wrote.

Opponents to dropping the rule warn that having Medicaid reimburse states for long term care in larger hospitals will blow up the Medicaid budget, costing as much as $1 trillion. They argue that states would reduce their spending on community care funding if given a choice between community programs and state hospitals.

The authors of the Manhattan Institute report argue the costs would be $5.4 billion spread over a ten year period and there would be no incentive for states to reduce spending on community programs.

Republicans attempted to eliminate the IMD Exclusion when former Rep. Tim Murphy (R-Pa) drafted the Helping Families In Mental Health Crisis Act. (Murphy was credited as an adviser to the Manhattan Institute Report.) But consumer groups, such as Mental Health America, and Disability Rights advocates strongly opposed ending the rule and Democrats successfully blocked Murphy’s language when his bill was incorporated into the 21st Century Cures Act in 2016.

Channeling the late D. J. Jaffe, who was a contributor at the Manhattan Institute, the authors argue that community based mental health services simply fail to help the seriously mentally ill who need long-term care to recover. Community services are failing this group, they argue, partly because of where they are directing their resources and efforts.

“As the number of diagnoses has expanded – and the number of Americans diagnosed at some point in their lifetimes with a mental disorder has increased – the number of claimants on public mental health resources has increased.”

In other words, what Dr. E. Fuller Torrey warned decades ago remains true.

We prefer to spend limited tax dollars and devote time to helping the “worried well” rather than those who need treatment the most.

You can read the full Manhattan Institute report here.

(Do you believe the IMD Exclusion should be dropped? Have you had trouble securing a hospital bed for someone in crisis? Would ending it hurt community services and turn back the clock to “snake pit” hospitals? Let me know your thoughts on my Facebook page.)

About the report’s authors:

Stephen Eide is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and contributing editor of City Journal. He researches state and local finance and social policy questions such as homelessness and mental illness. He has written for many publications, including National Review, New York Daily News, New York Post, New York Times, Politico, and Wall Street Journal. He was previously a senior research associate at the Worcester Regional Research Bureau. Eide holds a B.A. from St. John’s College in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and a Ph.D. in political philosophy from Boston College.

Carolyn D. Gorman is a policy analyst on issues related to serious mental illness and has served as a board member of Mental Illness Policy Org., a nonprofit founded by the late DJ Jaffe. She was a senior project manager at the Manhattan Institute for mental illness policy and education policy. Gorman served on the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions. Her writing has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, New York Daily News, New York Post, City Journal, National Review, and The Hill. Gorman holds a B.A. in psychology from Binghamton University and will graduate with an M.S. in public policy from the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service at New York University in 2021. Twitter: @CarolynGorm

From the report:

Medicaid’s IMD Exclusion was crafted for an entirely different era. During the last half-century, America built a system of community-based mental health services that did not exist in 1965. Income-support programs for the disabled, assertive community treatment, clubhouse programs, supportive housing, assisted outpatient treatment, supported employment, peer support services—these either did not exist in the 1950s, or they operated on a much smaller scale than now. Nevertheless, a small subset of severely mentally ill individuals still needs inpatient treatment on a short-term, intermediate-term, and long-term basis. The IMD Exclusion inhibits those individuals’ access to medically appropriate care. ..

March 10, 2021, 6-7 PM (MST)

Come learn from Dr. Michael Franczak of Copa Healthcare on Population Health trends in Maricopa County. He brings decades of experience into the conversation.

Register in advance for this meeting:

https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZclc-ysqTgvG9Cwq6lcdfpq8mLIl7mLxzvP

After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the meeting.

You must be logged in to post a comment.